views

This Christmas Eve, humans will try to embrace a star

When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

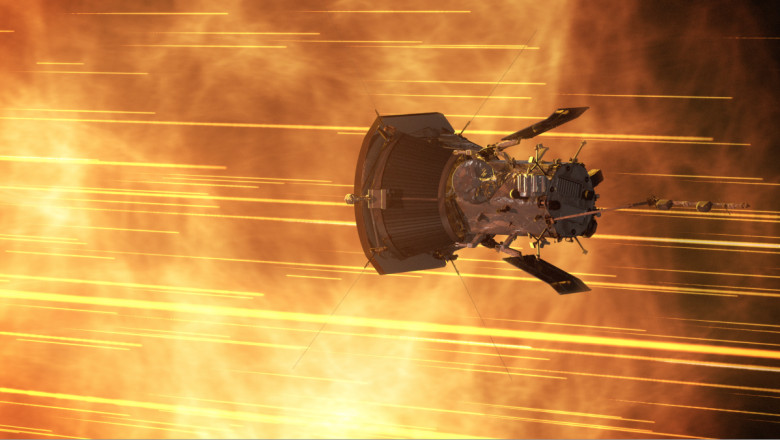

An artist's rendering of the Parker Solar Probe approaching the sun. | Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

There's this running debate among astronomers about whether our moon deserves a proper name. After all, it is the way of our solar system. Other moons each have monikers, like Phobos and Deimos, and there is certainly no planet named "planet" nor asteroid named "asteroid." Even worlds beyond our cosmic neighborhood have names, albeit often very boring ones. However, our moon's namelessness does have a silver lining: It forces us to remember that it is, indeed, a moon.

The same can't be said for the sun, whose name makes it easy to forget it's really an incomprehensible, scorching star. But on Christmas Eve this year, we'll be acutely reminded of the sun's cosmic nature thanks to a resilient little spacecraft on a spectacular journey through space: the Parker Solar Probe. On Dec. 24 at 6:53 a.m. ET, this conical explorer will fly dangerously close to none other than our glowing yellow sun.

"In 1969, we landed humans on the moon; on Christmas Eve in 2024, we are going to embrace a star," Nour Raouafi, project scientist of the Parker Solar Probe mission, told Space.com.

On Aug. 12, 2018, NASA launched the Parker Solar Probe toward the sun with the hopes of decoding a bunch of longstanding solar mysteries — perhaps the most perplexing of which concerns the fact that our star's atmosphere is weirdly hotter than its surface. What's heating it up? It seems unintuitive, doesn't it? In the audience on launch day was the late Dr. Eugene N. Parker, who revolutionized our understanding of solar physics before the solar probe began its expedition and indeed gave Parker its name to begin with; this marked the first time a spacecraft's namesake was present for liftoff.

Then, on Dec. 14, 2021, the agency announced that Parker Solar Probe successfully entered the sun's atmosphere, or corona, getting just about 6.5 million miles from the star's surface. This was monumental in itself, but since then, the spacecraft has continued to get closer and closer over 21 orbits around the sun, leveraging Venus' gravity to propel itself while breaking records left and right. For instance, it is officially the fastest-ever human-made object, reaching speeds pushing 394,736 miles per hour (635,266 kilometers per hour).

On Dec. 24 of this year, however, Parker Solar Probe will complete its closest pass to the sun to date, getting within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the object's surface while zooming at 430,000 mph (690,000 kph). Previous records will be shattered.

"What the Parker Solar Probe is about to do on Christmas Eve of this year is really unparalleled," Raouafi said. "We have been dreaming of this moment for over 16 years."

A giant sun is behind a little parker solar probe.

And, as Raouafi explains, this is likely as close as the probe will be getting.

"Even if technically we can get the spacecraft closer to the sun, we cannot do it because the heat shield is not big enough to protect the spacecraft," he said. "If you get closer, the shadow cone of the heat shield will be narrow, and potentially, parts of the spacecraft will be exposed to direct sunlight — and that's not something we want to do."

There's an aspect to Parker Solar Probe's journey that, at first glance, seems like it'd cause a stir among mission members: The spacecraft will be off the grid during the major flyby; we will have no way of contacting it.

Comments

0 comment